The Upper School (US) math department has discussed more than calculating derivatives in their math department meetings: the department is committed to reducing inequity disparities in the math department through its long-term initiatives to include students from underrepresented backgrounds in Honors and Advanced Placement (AP) courses.

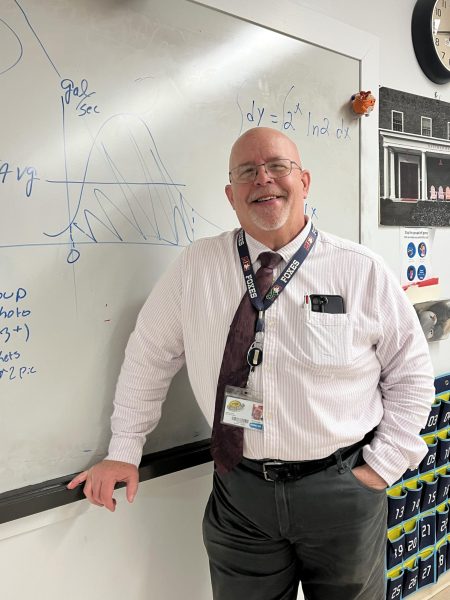

US Math Teacher Michael Omilian, who has taught at MFS for over 35 years, said that there has been a significant change over a long period of time from these initiatives.

“If you go back in the ’90s, it was rather unusual for students who were coming new to the school to ever be placed in an Honors or AP Class … we took a concrete look at that situation and we were able to fix it,” he said.

Throughout the years, the math department has strived to create equal opportunity for students to take advanced courses using an array of analytical methods.

The department examined data from new ninth graders to ensure that the transition to US math courses from Middle School (MS) is equitable for all students. They analyzed the correlation between math grades, students’ background, and their race and gender.

The department found that some incoming high school students had fewer opportunities in their middle schools to take difficult math courses compared to Middle School at MFS. According to Omilian, public schools’ “No Child Left Behind” policy put all students at the same level in math class without the opportunity for advanced courses. The No Child Left Behind Act was created in 2001 to improve public education through more accountability and standardized curricula.

This created an “innate inequity” between incoming ninth-grade students and ninth-grade students who attended MFS for Middle School, according to Omilian. Students who attended MFS had the advantage of taking advanced maths coming into high school and would be automatically placed in Honors/AP Courses.

Omilian said, “Because these students from other schools didn’t have that particular program, they were placed at a disadvantage. Unfortunately, that disadvantage tended to lean towards racial lines. School districts that were mostly composed of people of color did not provide honors or advanced courses to their students at that time in the ’90s and early 2000s.”

When placing students who come from disadvantaged backgrounds or identify as a marginalized person in their courses, the math department uses the students’ admission folders to look at their previous curriculum and achievement to “make an educated decision from there and not just from raw test scores.”

To enroll in an Honors or AP Math Course in the US, the department first considers the student’s math grades. Then, they must take a placement test and receive at least an 87% on the exam. The math department chooses who is accepted in Honors/AP courses based on these scores as well as “the situation the students are coming from,” according to Omilian.

The department “always keeps a student’s background into consideration,” according to US Math Department Chair and US Math Teacher Katie LuBrant. They support students who may need extra help before the advanced placement test or decision.

“[If] someone comes in and tells us their story of a bad night due to their family circumstances or their learning differences, we’re going to meet them. We’re going to meet them to give them help to catch them up.”

“I don’t want to say that color blindness is stupid because obviously you know what color and gender people are. But we try to because we’re a data-driven group. We try to keep the focus on grades and take the big picture into it. We want access for everyone who comes to MFS,” said LuBrant.

The math department has also tried to offset inequities when transitioning from MS to US by making Algebra 1 a required class for every eighth-grade student, as opposed to Introduction to Algebra.

According to LuBrant, this allowed for qualified students to transition smoothly to Honors in ninth grade if they wanted to, since Algebra 1 is a prerequisite for the ninth-grade Geometry class.

Without this system in place, where everyone was on an equal footing in eighth-grade math class, students would have to skip classes to take advanced courses later on in their high school career.

“[There were] more leaps and bounds that they had to go to cross,” said LuBrant.

As a result, LuBrant reported, “We definitely felt from the kids … that it was easier to make that transition.”

After these successful changes, Omilian said that the math department wondered if they were “unconsciously creating a system where certain [socioeconomic] classes were more advantageous going into an Honors or AP Class.”

Many rising sophomores choose to learn Algebra 2 over the summer to take Precalculus in their sophomore year in order to take advanced courses like AP Calculus in their junior or senior year. These students often have tutors to help them pass the exam that certifies their knowledge of Algebra 2. The math department flagged that there was a potential inequality in students with higher socioeconomic status’s ability to have tutors and extra resources compared to students who may not be able to afford those resources.

To combat this disparity, Omilian noted, “We [provided] financial aid. We tried to create an in-class program [as well as] peer tutoring. All these things were made to offset that inequity.”

LuBrant said that the department also did a “deep dive” in school data to see if the percentage of students of color and those who identified as female in the US population reflect who was enrolled in Honors and AP classes in the Math Department. They were looking to see if they were “involved in any kind of bias in granting those positions.”

She reported that the percentage of marginalized students in the US population enrolled in advanced classes was “very much aligned.”

In contrast, the number of marginalized students who continued to be in Honors/AP Classes by the time they graduated was not as aligned. According to Omilian, this was a data point that the math department is trying to improve by “meeting every kid where they are to support them in their efforts and being available to all students.”

He acknowledged, “No matter what you do, there’s always some inequity involved. We just try to minimize it.”

Additionally, the math department has also made a “conscious effort” to make Honors and AP Math classes more accessible to marginalized groups, according to Omilian. They often encourage students who are in College Prep (CP) classes that perform well to consider taking a more difficult class in the following year.

“When a student is performing well in their class and their teacher thinks they’re capable at any moment within the math curriculum, they are given that opportunity to advance. They can move based on their interests, maturity level, and their abilities,” said Omilian.

The math department strives to discuss social justice and diversity-related issues in current events during math class. For example, in LuBrant’s Precalculus class discussing exponential growth, she teaches about how the rising costs of some prescription drugs and EpiPens have made them unaffordable to people without proper insurance.

Meriwether recalled learning about insulin prices in his Honors Precalculus class.

“We did a question on insulin’s rising prices and how that impacts social classes … I think [current event related math questions] are interesting topics to learn more about because it’s important to get those prices of insulin lower and have more awareness so that more people know about these pressing issues in society.”

LuBrant said real-life math problems “make math more applicable to everyone instead of the random problems that are in some books.” She added, “You get different perspectives that you may not have heard before …[Students] can broaden [their] thinking and critical thinking skills.”

She said, “We strive as a department to meet every kid where they are to support them in their efforts, to be available to all students, to bring up social justice topics in our classroom when we can.”

Dy’lea Muhammad ’28 stated that these diversity initiatives in the math department have allowed her to “push [herself] to go farther in places like math.”

She added, “I feel like for me, because of how I am, I think math isn’t the best class for me, but I feel like the diversity efforts helping to push is important because I don’t want me in the future and other people to be discouraged because maybe it’s not normal to see people of color in challenging classes.”

LuBrant said that access to opportunities is “part of our values as a school — our Quaker values. So it has to be in our department.”