The Moorestown Friends School History Department is undergoing a significant transformation this year with the introduction of two new faculty members and plans for the rollout of semester-based history seminars next year.

The US History Department consists of four teachers—Mary Anne Henderson, Clark Thomson, Whitney Davidson, and Frank Karioris. The latter two are new members of the MFS community, and Henderson, the History Department Chair, began teaching at MFS in 2022.

Whitney Davidson: A Veteran Educator

One of these new MFS faculty members, Whitney Davidson, is a veteran educator with over twenty years of experience. Davidson has taught across the country, from the Boston area to California, with a consistent mission to help kids “see the joy that comes with learning” and to “create a high-energy environment where kids are excited to learn.”

However, Davidson’s teaching philosophy isn’t just the product of her extensive experience — it’s also deeply influenced by her own personal challenges, particularly her struggle with social anxiety.

“It might seem counterintuitive,” she shared, “but as someone who has struggled with social anxiety my entire life, teaching became my way of confronting that fear head-on.”

Davidson said she believes her openness about her teaching anxiety helps her connect with students who feel similarly.

“I try to embrace my own awkwardness in the classroom,” she explained, “and by doing so, I hope to create a space where students feel fully themselves.”

As an educator, Whitney’s vulnerability becomes a powerful tool in establishing an environment of trust and supporting students who have social anxiety just like her.

“I think being open about my anxiety makes it easier for students who also feel socially anxious to relate to me,” she added. By showing students that it’s okay to feel uncomfortable and that it’s a part of the process, she leads by example, fostering an atmosphere where authenticity and vulnerability are embraced.

Davidson’s dedication to fostering inclusivity is also visible in the way she views education as a collective endeavor. She strongly believes that education has the power to change lives, but acknowledges how hierarchical society at large can be, especially regarding access to education.

“Humans — as a collective — undermine our potential as a species by accepting how stratified our society is in so many ways,” Davidson explained. “We’ll never reach our full potential in terms of innovation and technological advancement because so many people remain mired in poverty without access to basic necessities, let alone a high-quality education.”

Civic engagement and social justice are also topics Davidson cares deeply about, a theme found among the teachers of the History Department. Davidson stated she puts an “extremely high premium on civic engagement.”

A cursory glance at Davidson’s room backs this statement up: on the board behind Davidson’s desk is a sort of banner with the words, “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free,” a quote from famous civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer.

When asked about her decision to put this banner up, one of the few decorations Davidson put up during her first few days, Davidson explained, “I see my role as empowering students with knowledge so that they can make informed choices and think critically. Once I started learning, my whole world opened up … I want my students to have that same experience.”

Davidson elucidated her thoughts on the connection between education and freedom. “I connect that to sort of like learning and literacy and how freedom stems from that process,” she said.

Davidson, whose “close family” counts Quakers among themselves, mentioned being intrigued by MFS’ Quaker values and commitments to community and respect for community voice.

“I love the atmosphere here,” she said, on her initial impressions of MFS. “I’ve been feeling really welcomed. The student engagement is so high, and the respect they show to each other is something you don’t see everywhere.”

Davidson ended her interview with one request she wanted to share with the MFS community at large — “If you happen to see a beautiful bird, I would love to hear about it.”

Frank Karioris: A Global Citizen

Dr. Frank Karioris, also new to MFS this year, has taken a much different road to MFS, one that crisscrosses the globe. Originally from Milwaukee, Karioris has taught across Europe, Central Asia, and South Korea before arriving back home in the States to teach at MFS. His academic background is rooted in gender studies and sociology, with a particular focus on masculinity and social relationships, which was the topic of his dissertation in 2016.

Karioris’ research for his PhD, done at Central European University, involved ethnographic fieldwork with first-year college students, many of whom were grappling with questions about identity and masculinity. As a researcher, Karioris found that these young men often sought clear-cut answers to complex questions, looking to him as an authority figure for guidance.

“There were moments when they wanted me to tell them what it means to be a ‘good man’,” Karioris recounted. But rather than give them the answers they desired immediately, Karioris’ role as a researcher was to step back and let them navigate these questions themselves. “As a human, I wanted to help them,” he explained, “but as a researcher, I had to let them learn on their own terms.”

This approach translates directly into his teaching style, which, like Davidson, is based on his own life experiences. In the classroom, Karioris often practices what he calls “sitting in silence” after positing a question, allowing his students the space to think deeply before responding, much akin to how Quakers use silence.

“Sometimes, teachers are so eager for their students to learn that they jump in too early and answer the question themselves,” Karioris noted. “But if you let the silence sit on for a moment longer, you’ll often find that students come up with more thoughtful, complex responses.”

“My work is about trying to understand people in their environments, which often means allowing them the space to answer the big questions for themselves,” Karioris said. “The role of the educator is to provide students the opening to do their job — to think and learn critically — and to step out of the way when necessary.”

Karioris’ global perspective has also played a crucial role in shaping his teaching style and his approach to curriculum development. As a part of the new seminar-based curriculum, he’s excited about the opportunity to break out of traditional bubbles and dive deep into niche areas of history.

“Seminars force us outside of our comfort zones,” he said. “For example, we could explore contemporary South Asia, not just with a superficial glance at Gandhi but by understanding the deeper complexities of figures like Nehru or Ali Jinnah. These are opportunities for students, and for me, to continuously learn.”

When he asked what he would like the community to know about him, Karioris shared his personal learning goal for the year. As someone of Greek heritage, he is immersing himself in the works of four major 20th-century Greek poets: CP Cavafy, Yiannis Ritsos, Giorgos Seferis, and Odysseas Elytis. “These poets represent not just Greece, but the diaspora of Greece,” he explained. “Cavafy, for example, lived in Alexandria, Egypt, while Seferis was born in Smyrna, now part of Turkey. They grappled with questions of identity, history, and belonging, which are topics I hope to bring into my teaching.”

For Karioris, these poets offer insight into the complexities of being Greek in the 20th century, a time when national boundaries and identities were fluid and contested.

“It’s a personal goal I’ve set to read through these poet’s works, and I’ve shared it with my students so they can support me in my learning journey,” he added. This commitment to continuous learning is something Karious feels strongly about in both his personal life and his teaching philosophy. “If I’m not learning in the classroom, then it’s not a very good class,” he said. “Learning should always be collaborative.”

Reimagining History: A New Seminar Approach

Mary Anne Henderson, the History Department Chair, is a fairly recent addition to the MFS Faculty; they began teaching at MFS in 2022. While some may correlate the new changes to the history curriculum with Henderson’s arrival, the overhaul predates Henderson’s tenure. Tasked by the collective department with guiding the shift toward a seminar-based structure, Henderson speaks passionately about a more immersive, student-driven approach to learning history. Rather than adhering strictly to “chronological form[s] of history”, the new curriculum encourages students to develop critical thinking skills and approach history thematically, with a focus on how to “do the work of a historian.”

“This has been a long time coming,” Henderson emphasized, noting that the idea for the seminar program began before her arrival. “We want our students to leave MFS with a set of skills, not just knowledge of specific historical events. We want them to be able to do the work of a historian — asking questions, comparing sources, and thinking critically.”

Clark Thomson, Henderson’s predecessor and current history teacher, affirmed Henderson’s timeline.

“Eliza McFeely and I began working on that … before the pandemic with the hope of rolling it out to … Academic Council as a proposal moving forward. The pandemic got in the way of that, Eliza retired, and we were in a sort of transition period.”

Thomson went on to explain, “When Mary Anne was hired, I mentioned that this was something we were thinking about.” Thomson complimented Henderson’s willingness to take on the project, and their immediacy to do so, noting that they “[began] the next phase.”

Thomson classified the behind-the-scenes work to implement semester-based seminars into two phases, the pre-Henderson phase and the during-Henderson phase. The former phase was “three years” long, and the latter currently stands at two.

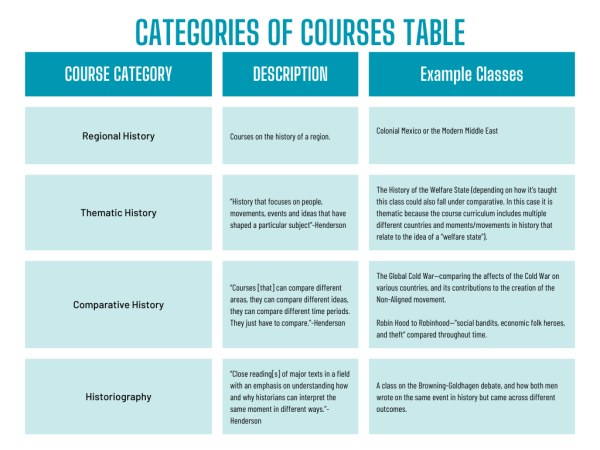

Open to 10th, 11th, and 12th graders, these seminars cover a wide range of topics, which fall into four main categories: regional history, thematic history, comparative history, and historiography.

“We’ve developed a philosophy and an approach,” Henderson said, “that has guided the creation of the seminar program.” These semester-long courses are similar to the English Department, a similarity noted by Henderson. They added, “The idea is to teach students not just history content, but how to be a practicing professional in our field.”

Henderson described regional history as, “contain[ing] chronological history topics. Courses may focus on one period of time in one country or focus on a region … [F]or example, you could expect a colonial Mexico class or a modern Middle East class … modern topics would count as well.”

Henderson elaborated on this description by saying, “There’ll be a mix of modern, early modern, some ancient, and then global engagement.” Henderson defined this last category as, “a blend of US history and courses around the world so … that you’re not ending up with a really sort of narrow scope of offerings in any given year.”

Henderson defined thematic history as a, “more integrated approach to the study of history — history that focuses on people, movements, events, and ideas that have shaped a particular subject.” Henderson clarified, “Thematic history does not adhere to a linear progression. It may move back and forth through time and space to fully reveal the processes and factors that inform historical change.”

An example they gave that could fit into this topic was a class about welfare states. “[The content in the class] ranged all the way from the creation of the welfare state and the United States after the Civil War with the rise of sort of like medical care for the Civil War vets, all the way to the modern era, and …Thatcher and Reagan and the dismantling of the welfare state, but it also went to … the Scandinavian countries. And so it was comparative, but the theme was welfare states, right? And we moved back and forth through time,” Henderson explained.

Henderson described the third type of course, comparative history, as, “courses [that] can compare different areas, they can compare different ideas, they can compare different time periods. They just have to compare.” Henderson noted that the welfare state class could also fall under this category, but they gave the additional example of a class on the global Cold War: “Looking at the way the Cold War affected, impacted and was prosecuted by places all over the world, bringing in right, the idea that it’s not actually a bipolar conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States, but instead involves the rising of the non-aligned movement.” Another example Henderson gave, that they noted being particularly excited about, “is from Robin Hood to Robinhood… Social banditry, economic folk heroes, and theft. So looking at and comparing bandits, pirates, and outlaws in [the] past.”

Courses on historiography, the study of the field of history, were detailed by Henderson as classes that may include, “close reading[s] of major texts in a field with an emphasis on understanding how and why historians can interpret the same moment in different ways.” Henderson gave an example that they recall going over in grad school—the Christopher Browning and Daniel Goldhagen debate. Henderson explained how a course on the debate would work. “We’d read two books about the same thing that make really different arguments, [such as Browning] and [Goldhagen].” Henderson explained the backstory behind the debate: “Goldhagen writes this book called Hitler’s Willing Executioners. Christopher Browning wrote a book called Ordinary Men, also about Germany and the German secret police and the prosecution of the Holocaust. And they both have very different arguments about why normal, regular people participated in the Holocaust. So Goldhagen comes from a place very particular to Germany and the German mindset. Browning’s coming much from the place of the particulars of human psychology—and therefore this is something that could happen again.”

Henderson also mentioned a class on the subject of historiography titled “Hollywood History.” “So like watching films about the Vietnam War, which changed drastically depending on the era that we’re looking at them, from John Wayne to Apocalypse Now to Platoon,” Henderson excitedly explained. “We could do another one with the same Hollywood theme, but looking at the Department of Defense in Hollywood and the way that they interact. So it’s basically the text can be both an actual physical history book [or anything else],” Henderson said.

Each seminar will focus on a unique approach or theme, whether it’s concerning a specific region, comparing different periods or movements, or exploring how historians interpret key moments. To ensure students get a well-rounded education, Henderson and the department are carefully coordinating to prevent too much overlap. “We don’t want to end up with a year where we accidentally offer only U.S. history courses,” she explained, stressing the importance of balance in the course offerings.

This new structure would do away with the traditional three senior history courses, instead offering a set of junior-senior semester courses. Thomson, who currently teaches Honors Economics, one of the three senior history courses, said that the lessons taught in economics would still live on in new courses.

“As I’m designing classes to propose to the department, I’m thinking about what parts of [economics] could go into a class that was focused on more of a real-world situation.” Thomson gave the example of a class on the financial crash of 2008, saying it would “look at the economic side, it would also look at the social side, it would look at the political side as well … I would choose things that are clearly economic in basis, so the primary piece would be learning the economics of it.”

While noting that there are pros and cons with both the current iteration of his economics class and the future proposed versions, Thomson acknowledged feelings of a net positive for the switch, and said, “It’s going to be an exciting journey.”

10th graders, unlike 12th and 11th graders, would have a separate list of courses by themselves. Henderson noted being interested in offering the same semesters years in a row, in order to give students who didn’t get their first choice the opportunity to try again the year after.

It is important to note that students taking AP US History would be exempt from that year’s seminar requirement; the existence of other history AP classes offered by the history department is a matter of current conversation. Henderson emphasized that the details of the program are still under review and will be finalized after being approved by the Academic Council.

Another benefit of this approach, according to Henderson, is the flexibility it gives students.

“A student might decide to double up on sciences one year and then focus on history seminars the next,” they pointed out, which would allow students to tailor their schedules to their interests.

Karioris highlighted a potential positive reciprocal effect of next year’s transition to semester-based seminars: “[This approach] forces [teachers] to be open to not just civics and social justice, but also stepping outside of our bubbles to engage in more niche, focused areas of interest.”

Finally, Karioris tied the two positive positions together: “[This new approach] keeps both students and faculty from falling into stultifying, stagnant traps, pushing us to stay on the front of our feet.” Karioris ended his thought with a statement backed by Davidson, Henderson, and Thomson: “If we’re in a classroom, we should be learning collaboratively.”