The Stokes Hall Timeline: A Brief Introduction

By Ali Benjamin ’23 and Amir Mashaqi ’23

On the morning of November 4, 2022, students and faculty were met with a surprise as they entered Stokes Hall Lobby. Overnight, the maintenance team had removed the lobby’s central display — a historical MFS timeline — after concerns of offensive imagery in the panel featuring the 1960 Mock Political Convention were brought to the administration’s attention.

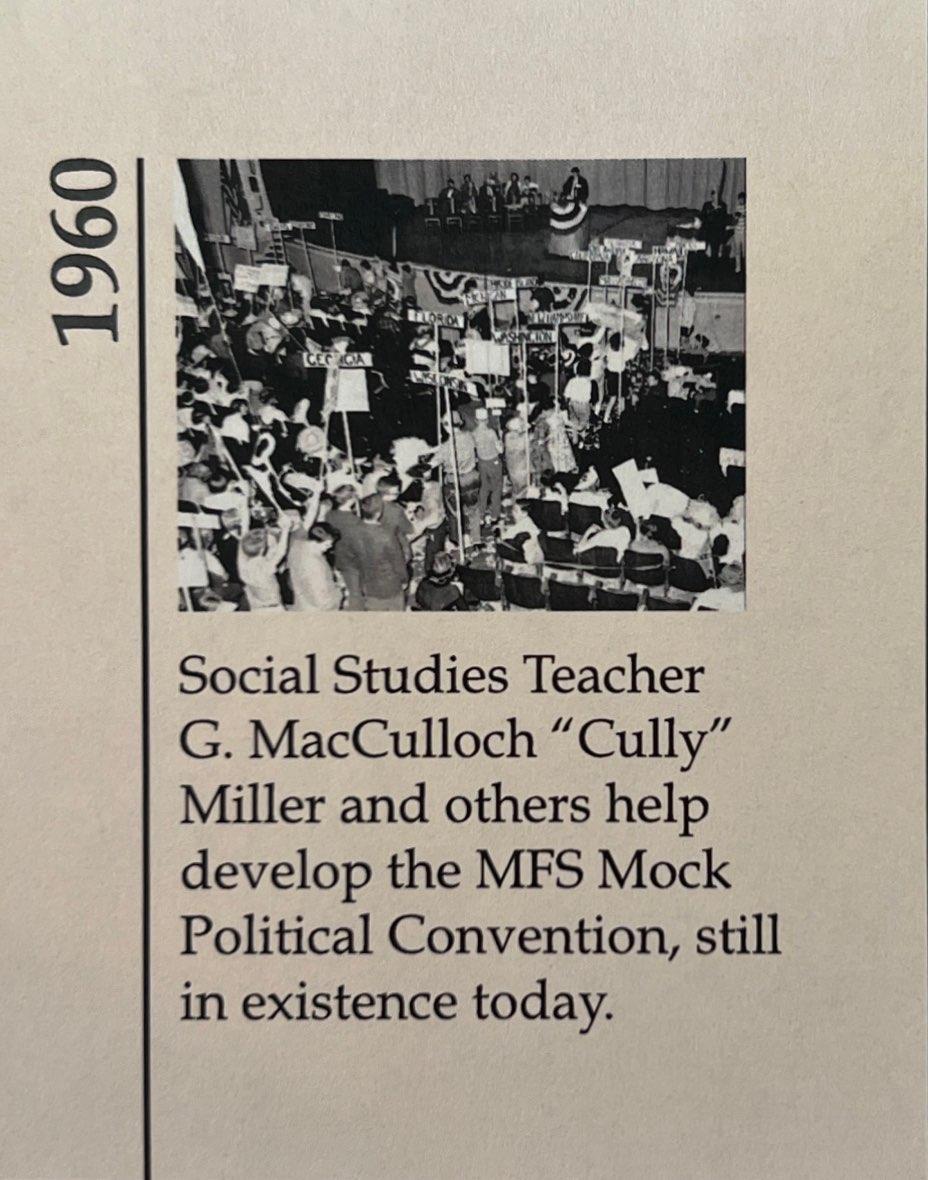

The timeline of events significant to the history of Moorestown Friends School was designed and installed over a decade ago, but at the bottom of the fourth panel of the display, community members recently noticed three students holding what appeared to be Confederate battle flags. (Image: A picture of the panel in question. Photo by Ali Benjamin ’23.)

The Mock Primary Election has been a valued Moorestown Friends tradition since 1960. For the first forty years, the event was titled Mock Political Convention, but was renamed in 2000 to “encourage students to understand the impact that they can have on the direction of their nation,” according to event coverage from the 2000 yearbook. Spearheaded by former social studies teacher G. MacCulloch “Cully” Miller in 1960, the Mock Primary Election is now run by US history teacher Clark Thomson.

60 Years of Modeling Democracy: A Visual History of MFS Mock Primary Election

By Luke Iacono ’25

With additional reporting by Sophia Lalani ’25

Students Speak Up: Upper School Community Reactions

By Julia Tourtellotte ’23

“Just get rid of this picture; it doesn’t matter what goes there to replace it. It just needs to be taken down,” said Maya DeAndrea ’25.

The discovery of the Confederate flag image in the timeline led to many strong emotions and opinions from students. Many were disturbed and confused as to how the photo could have gone unnoticed for so long. Because the flag in the panel image was only partially visible, the type of flag that students held was unclear. Community members theorized that the flags were Georgia state flags from that era, not traditional Dixie flags, since the students holding the flags in the photo were near a sign that said “Georgia.”

At the time, the Georgia flag included the popularized Confederate battle flag – formerly the Dixie Flag – in its design. While Georgia removed the Dixie Flag from its design in 2003, according to MSNBC, there are still five states that have flags with Confederate symbols: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Mississippi, and Georgia (which still has other Confederate imagery in its design).

Some students, while disappointed at the photo, also recognized its historical significance: “I was shocked at first, but not super surprised. It’s a historical timeline, so there was bound to be something like that in it,” said Andrew Zhou ’25.

Zhou elaborated on his thought: “A lot of people kept asking why the Confederate flag was in the timeline, and people seemed to be confused as to why it wasn’t caught before. I clarified [to them] that it was from a mock election with the Georgia flag. Many former Confederate states had the Confederate flag in their flag at some point in time. Obviously this doesn’t defend the flag being there, but that was most likely the reason why.”

Many students shared similar beliefs and brought their opinions to agenda to discuss the matter. Miles Wilkins ’25 said he felt that regardless of the flag’s true nature, the community should prioritize making members feel comfortable and safe. He said, “I voiced my opinion at agenda, basically stating that if members of the community were offended by the timeline, why is it even up for debate for what to do with it; why don’t we just immediately remove it?”

“Just get rid of this picture; it doesn’t matter what goes there to replace it. It just needs to be taken down,”

Maya DeAndrea ’25

DeAndrea stated, “I was disappointed that it was still on display in our school because it was portraying a negative message that our school doesn’t support.”

Additionally, students discussed what should be done with the image, and the consensus was relayed to administration. Ultimately, an “administrative team,” according to Head of School Julia de la Torre, decided to remove the timeline entirely. Other alternatives such as a “digital timeline” were proposed, however some community members looked unfavorably upon this option. Zhou believed that “a digital timeline removes a lot of character and looks out of place.”

Overall, the community supported the removal of the timeline. However, students, such as Wilkins, recognize that preventative measures must also be taken: “To prevent things like this from happening in the future, there should be a review of all imagery on campus. I think we as a community must be aware of the meanings of different symbols and their implications.”

Additionally, DeAndrea recognized the importance of the implication of the imagery, and the effect it could have had on the community if not handled in a more timely manner: “I hope the community can address these issues quicker because the timeline was up for a long time before anything was done about it, and I hope we are not portraying negative messages that we do not believe in at our school.”

The Power of the Flag

By Dinah Megibow-Taylor ’24

“It’s so interesting … the power of flags,” mused vexillologist and former MS/US history teacher Steven Baumann.

Confederate imagery, and most notably, Confederate flags, are ingrained into national symbolism in the present day. This imagery comes with the baggage of vehement sedition and racism, but it constitutes a major part of American history. The power of flags – including the Confederate flag – is mighty, and flags have always been used as points of nationalism, pride, and strength towards their respective causes. The Confederate flag is no different in its inherent pride for the Confederacy. But what did it mean in the context of the Georgia state flag of 1960? How does that symbolism carry into the present day?

Baumann argued that generally, discerning symbolism “can be quite complicated, not only because of what things mean in the past, but what things mean in the present.” There is often a meaning that is “injected into the flags from the present” that intensifies or even shifts their narratives. “I’m a firm believer in people having the agency to make the meaning of the flag, of the symbol,” he said.

Even into the Confederate flag, Baumann recalled, many different meanings were “injected.” “The Confederate battle flag was popular among Irish Republican Army members. [Some] people saw the Confederacy not as a racist institution, but as one that rebelled against authority figures.” Though this interpretation does not change the racist connotations of the symbol, “You get these weird crossovers where the Irish Republican Army, you would think, is nominally fighting for rights for people who are being suppressed by an empire, then adopting this hateful racist flag. So it can be tricky at times. And it does get complicated. So you have to be aware of what context it’s being flown in.”

“I’m a firm believer in people having the agency to make the meaning of the flag, of the symbol.”

But, more often than not, especially in the present day, flags are catalysts of national symbolism. In terms of nationalism, those in defense of portraying the Confederate flag argue it as an integral symbol of freedom and of rebellion against the oppressive federal government of the United States and therefore standing for individual liberty – the core American value. Those against it argue that it is the antithesis of nationalist or patriotic symbolism; it is simply a symbol of vicious sedition and of the practice of slavery. More generally, “any national symbol … furthers political perception. People seem to love [flags], putting them on their cars, in their offices, hanging them up,” said Baumann. “You know, there was a time where every classroom and every school had an American flag. You know, the Pledge of Allegiance was a thing [in schools], and that’s kind of gone out of style. But the American flag certainly hasn’t.”

And in some parts of the country, the Confederate flag has not, either. “It really shocked me when I was in the Northeast to see more Confederate flags, almost than I would see in the South,” Baumann remarked. “In the South, you have [Confederate symbolism] kind of ingrained in the cultural heritage where [it was] the same institution [as the Confederacy] itself. It was only until 2020 that South Carolina was still flying the Confederate flag … whereas in the Northeast, I’ve seen a lot of individuals, just people in upstate New York who are flying a Confederate battle flag, which just is, to me, a way of them saying they’re racist.”

Though different, Baumann raised the example of another state flag, the Arizona state, as a flag that has received significant criticism. “It received a lot of pushback because Arizona’s flag without the sun … looks a lot like South Vietnam’s flag used to. And there’s a lot of Vietnam War veterans [t]here who didn’t want to see that hanging up everywhere. Now, if you [didn’t] fight in that war, if you didn’t know anyone who fought in that war, you might just think, ‘Oh, it’s a beautiful flag.’ But if you have a connection to Vietnam, that might, you know, be a triggering thing to see everywhere. So for different people, it definitely means different things.”

But what about the Confederate flag on the timeline, specifically? In fact, the imagery of the Georgia state flag in 1960 was not the official Confederate flag. Instead, it was the Confederate battle flag, the Dixie Flag, which is the flag that is nearly always associated with the Confederacy. That flag, said Baumann, “was a racist dog whistle, and … a symbol of hatred and racism … It’s pretty clear it’s [still] used by racists to put forth racist ideology.”

The “official” Confederate flag, though, is hard to place. “The Confederacy went through a number of different flags. There was never just one Confederate flag,” Baumman observed. “It shows how disorganized the Confederacy actually was. They couldn’t even come up with a flag.”

The journey of developing the Confederate flag, explained Baumann, was complicated and jumbled. “[The Confederacy] knew they didn’t want it to be American. They didn’t want it to look like the stars and stripes that we know. And so they came up with what were called the ‘Stars and Bars,’ which is a red, white, [and] within the corner, a blue field.” The ‘Stars and Bars’ flag became the official variant of the Confederate flag, adopted in 1861. “And what’s interesting is that that’s still the design of the Georgia state flag,” Baumann added.

But the use of national symbolism in general at the Mock Primary Election, and especially the use of symbolism that is rooted so firmly against the Quaker testimony of equality, Baumann posed, should be questioned as a community. “At their heart, Quakers are iconoclastic. They’re against symbols … The meetinghouse doesn’t steeple. There are no frescos on the wall. There are no stained glass windows. In fact, some of the stained glass windows, even [the ones] in the entryway of the Upper School, some Quakers might say that you’ve gone too far.”

“Was it the responsibility of those participating in American politics to reject [the symbols]? I think if you talk to some of the civil rights leaders, they would say absolutely … We could have used some help in putting these hate symbols away back in the 1960s. And maybe that’s the case, currently. But it’s a really challenging thing.” Globally, symbolism attached to rhetoric that is considered hateful or dangerous, including the hammer and sickle in post-Soviet nations, and the swastika in Germany, merit criminal punishment. There is not a “clean resolution,” said Baumann, to the display of negative historical expression.

“The Magnitude of Voices”: The Impact of Student Voice at MFS

By Dinah Megibow-Taylor ’24

Student voice played a tremendous role in deciding the fate of the timeline. Originally, it was students who brought the concern of the timeline into broader community discussion, and it was the action of student voice that ultimately brought it down. The main role of 2022-23 Agenda co-Clerks Andrew Mercantini ’23 and Haila Desai ’24 is to facilitate the expression of the range of student voices and guide the student body towards consensus around community matters. This instance highlighted the power of student voice and the forums in which they’re amplified. WordsWorth gave Mercantini and Desai the chance to reflect on their role in the process of removing the timeline.

Mercantini stated that, at first, the timeline was “something that came up, actually, through an English class, and then it got back to [Haila and me], and obviously, it was something that we wanted to handle swiftly.” Once the Clerks were acquainted with the issue at hand, they were able to bring it to their weekly Clerk Meeting, which consists of the six student government clerks and the four student government faculty advisers. “We were actually very surprised to hear that [some] faculty knew about [the timeline],” said Desai. “They gave us options of ways to cover it up, but we were told that we were not going to be able to get rid of it.”

A special commemorative decoration for a milestone anniversary of MFS, the timeline served both as a functional divider between the Stokes Hall waiting area and the two single-stall bathrooms, as well as a piece that told a story of MFS history. Head of School Julia de la Torre explained, at the beginning of discussion with an administrative team before the Agenda meeting, the hope was, while eliminating the panel in question, to “preserve the rest of the timeline instead of taking it down. [Later] we realized that was problematic.”

Though Mercantini and Desai were told that taking the timeline down was not an option, they took the issue to Agenda and presented the community with alternative ways to ameliorate the concern. Student response, the Clerks agreed, was emotionally charged and empowering. “I think a lot of times, there are often issues that are overlooked surrounding race or gender or sexuality. And [the timeline] was an issue that the entire student body seemed to care about,” said Desai.

“It felt really good … to get the community [together] on something that everyone was passionate about,” added Mercantini.

At first, students tried to offer some suggestions for covering up the offensive imagery so that the entire panel did not have to be removed, but students began speaking strongly about removing the imagery instead of covering it up. It was with this passion in Agenda Committee that a change in approach was made and what called for the Clerks to re-approach faculty. “After Agenda, [Mercantini and I] made the commitment … to go to [the Upper School student government advisers] and try and get [the timeline] taken down,” recalled Desai. The next step in the process was to sit down with faculty and attempt to, with the added power of student voice, get the timeline dismantled.

“[Mercantini and I] are two students out of two hundred,” said Desai. “The gravity of the situation, the magnitude of voices that followed, that was what made the change.”

“[Desai] and I went back to the problem and said, ‘Okay, even though we can’t figure out what we want to replace it with, we need to take this down,’” said Mercantini.

Ultimately, it was the further input of student voice, Desai said, that made it clear to faculty that students saw the dismantling of the timeline as the only appropriate action. After the Agenda meeting, “I was sitting with our [student government] advisors … and two other students came up to them before we started talking … and they were talking to [US Director Noah Rachlin and DEIB Coordinator Dot Lopez] about taking it down,” Desai recalled. “That was, I think, was what really made the difference, that students who did not usually go talk to faculty … talked to faculty, and then we … discuss[ed], and the next morning, we got the email that it was taken down.”

The faculty, Mercantini commented, were “really good at acting when [the community] needed [them] to, and hearing the … passion in Agenda.” After hearing student voices, the administrative team was willing to evaluate options that were previously unavailable. The shift in thought was spurred by the discontent that students had with the proposed remedies. “They brought up really good points,” noted de la Torre. “We talked about it as an administrative team and realized that maybe the only solution was to take down the whole thing, but that meant we had to take down the whole timeline, we couldn’t just take down one panel … then it wouldn’t really be a timeline anymore.”

Both Mercantini and Desai reflected that this conversation was one of, if not the most, impactful and fulfilling discussion they have facilitated, and that the breadth of student voice was what the Committee encourages. “I think Agenda Clerks are often seen as aligned with faculty, which is something that I take issue with,” remarked Desai. “Our job is to literally be the voice of students so that faculty can hear, and so … the more student voice in Agenda meetings really does make a difference.”

“[Mercantini and I] are two students out of two hundred,” said Desai. “The gravity of the situation, the magnitude of voices that followed, that was what made the change.”

Offensive Imagery is Everywhere

By Livia Kam ’26

Offensive imagery can be seen around the world through logos, images, flags, and mascots, to name a few. With our rapidly evolving society with different definitions of “offensive,” people all around the world try to raise awareness of these controversies and prevent history from repeating itself. Here are two examples of New Jersey schools that have tackled controversial imagery through a mural and a mascot:

Cherry Hill East

On March 23, 2021, Cherry Hill East High School (East) painted over a controversial mural depicting a “Chinese man with slit eyes, Manchurian pigtails, and a dumbfounded expression,” according to Eastside Online. The mural was painted by a famous Disney animator and alumni of East, Eric Goldberg ’73.

Alena Zhang ’23, a student at East, spoke of the mural: “There were disputes over the painting because it offended Asian Americans. [Goldberg] was quite famous in the animating world at Disney, so East was deciding between painting over a ‘piece of history’ or keeping it — even though it contained offensive imagery.”

According to an Eastside Online article, after extensive deliberation between Dr. Dennis Perry (East principal), student leaders in Asian culture clubs, and East’s Student Government Association, East decided to completely paint it over. (Image: The repainted mural. Photo by Livia Kam ’26.)

According to Dr. Perry from the same Eastside Online article, removing the mural was the best solution. If East were to only paint over the right side of the mural which depicted the stereotypical Chinese person, it will continue to “stir the pot” and prolong the situation.

Reactions to the removal of the mural varied. East students were split 50/50 between supporting and opposing the imagery, according to Zhang. “A lot of kids also just didn’t really care. I don’t think it affected most people’s normal school day at all,” said Zhang.

It’s important to acknowledge that the mural was painted 47 years ago, meaning thousands of students passed by it daily without noticing or pointing out the stereotypical depiction of a Chinese man. Even East’s Principal said he had “passed by that mural hundreds of times … blended into the landscape of the building,” according to Eastside Online. Dr. Perry said that people often do not look at things critically, which perhaps may explain how people might overlook the deeper meaning of the mural.

Pascack Valley High School and Pascack Hills High School

In June 2020, the Pascack Valley Regional High School District Board of Education unanimously voted to remove the names of the Pascack Valley High School (Valley) mascot “Indian” and the Pascack Hills High School (Hills) mascot “Cowboys.”

The Board of Education sent a public statement on June 23, 2020, which announced the removal of the “Cowboy” and “Indian” mascots for Pascack Hills and Pascack Valley High School. According to the statement, discussion from students, faculty, and administration presented concerns regarding how such mascots are “not in line with the district goal of equity and inclusivity.” Their intent is to respect and educate their community on the “mutual contributions of all races, genders, religions, and cultures.” They stated that they will identify new mascots that concur with the Pascack Valley Regional High School District with student, staff, and community members’ input.

“We’ve been the Indians ever since the school was built, and so were the Cowboys at Hills,” said Emily Moy ’23, a senior at Valley, “[Our mascots] are almost built into our culture and traditions.”

But why did the District Board decide to remove these “historical” mascots in the first place?

For Hills, it’s because the Cowboys were not gender inclusive to girls and excluded people of color. There was also a concern of rivalry between the Hills and Valley as naming two schools’ mascots in the same district after the children’s game “Cowboys and Indians,” according to an article by the Trailblazers. This game involves mock gunfights between cowboys and Native Americans. Mascots for two high schools of the same district should not be contrasting, but rather unifying both high schools.

For Valley, it’s because having Indians as a mascot was offensive due to false stereotypes. Before removing the name Indians as a mascot, Native Americans were seen as logos on school merchandise and Valley’s previous newspaper named “The Smoke Signal.” Native Americans with headdresses were marketed and fetishized as a logo. Valley’s football game chants are often considered racially insensitive from mocking traditional Native American chants.

The school spirit of the Indians follows Valley alumni, as explained by Moy: “One time I saw alumni of Pascack Valley and he asked me if I went to Valley and then he said, ‘Yeah, I’m still an Indian at heart!’ I was shocked,” said Moy, “Generations of families have all been to this school.” According to Moy, at least half of the teachers are alumni. Many parents and faculty members of Valley are also opposed to the removal of the name Indians as the school’s mascot.

On the other hand, some Valley alumni are embarrassed to tell their friends about their school spirit because of their racist connotations, according to Hill’s newspaper “Trailblazer.”

The Indians’ mascot does not represent or honor Valley’s Native American population or culture. “Only one Native American person has gone to our school within the last five years,” said Moy. And when The Valley Echo asked local Native Americans if they thought using Indigenous people as a mascot and logo was acceptable, they believed that using Native Americans as a mascot is offensive to them as it promotes false information about Indigenous culture.

Student Reactions

The decision resulted in two hours of public commentary during the online Board of Education meeting from both schools’ communities, as well as hateful comments in the comment section of Valley’s school newspaper’s Instagram, “The Valley Echo.”

Moy attended the District Board meetings: “We usually get no public comments, but when the mascot was removed we had two hours of public comments which was crazy. I would say most people that spoke at that meeting were in favor of removing it.”

While the majority of the members at the meeting favored removing the mascots, most of the student population at both high schools was infuriated by this decision.

The Valley Echo’s Instagram was bombarded with 1,800 outraged comments. These comments included fake users with inappropriate usernames such as “George Floyd, Sacagawea, and Pocahontas,” according to an article by NorthJersey News. This led The Valley Echo to disable their comments while acknowledging the concerns of censorship: “The comments were not removed because they heard people disagreeing with the decision regarding the mascots and they wanted to stifle opinions,” said Spencer Goldstein, then a student and Editor-in-Chief of “The Smoke Signal,” in the article: “It was shut down because people took it too far.” Some comments were so hateful that the administration of the school had to report them to the police.

In a poll made by The Valley Echo, 67.4% of students at Valley believed their Indian mascot should not be changed. 641 responses were collected, which was about half of Valley’s high school population.

Protests emerged from outraged students who were against the removal of the mascot names. Some signs read: “Defund the Board of Education!” “TRUMP – Make Hills Great Again!”

Protestors passionately spoke of their stance on the controversy, according to the Trailblazers: “Who’s going to pay to rip up the endzone [of the football field]? That’s the name that we pay for! We spend hours paying for that, and now you’re taking it away from us without our choice!” “This [protest] is what the majority looks like.”

Decision-Making Process for a New Name

The Pascack Valley Regional High School District Board of Education voted 5-4 in favor of approving the new mascots at both Valley and Hills on March 8, 2021. A new committee was formed called the “Logo Selection Committee,” which consisted of representatives from every club or team at Valley and Hills. This committee was tasked with choosing a new name and logo for both schools. They decided on the Broncos for the Hills and the Panthers for Valley.

What Now?

After spending $300,000 to rebrand both schools and athletic facilities, there isn’t much pride in their new mascots. “Honestly, I feel like there isn’t much Panther pride,” Moy explained, “Even though we aren’t the Indians anymore, I still feel the culture.” According to Moy, the cheerleaders don’t even say “Go Panthers,” but instead “Go Valley.”

From the ferocious backlash from the removal of two offensive mascots to the trials and tribulations of deciding on new mascots, it is definite that Pascack Valley and Hills High School have thoroughly considered their remnants of culture, tradition, and legacy.

Conclusion

Cherry Hill East High School and Pascack Valley and Hills High School both possessed offensive imagery that had been a part of their school for almost the entirety of the school’s existence. But why have these communities waited until 2020 and 2021 to address such controversial imagery?

Mary Anne Henderson, MFS US History teacher and History Department Chair, stated, “I feel we’re in a racial reckoning period that begins to acknowledge racial inequality. This comes out of a long history of protests and anger toward this matter. This particular reckoning period that we are currently in starts with the violent murder of George Floyd in 2020.”

Henderson continued, “Although we’ve had many ‘racial reckoning periods,’ the United States continues to memorialize racists. In this particular era, people are attacking the symbols of racial inequality, especially in police brutality.”

Some examples of the effects of these protests were the removal of Confederate statues and monuments that supported the enslavement of Black Americans, as well as changes in the education curriculum in the US and UK. Students wanted to learn about colonial imperialism and its impact on the people who were colonized or enslaved.

Henderson supported this progressive way of teaching: “I think it’s healthy to confront the good and the bad while learning about our past. It becomes a way to validate marginalized students as opposed to gaslighting them into ignoring their past.”