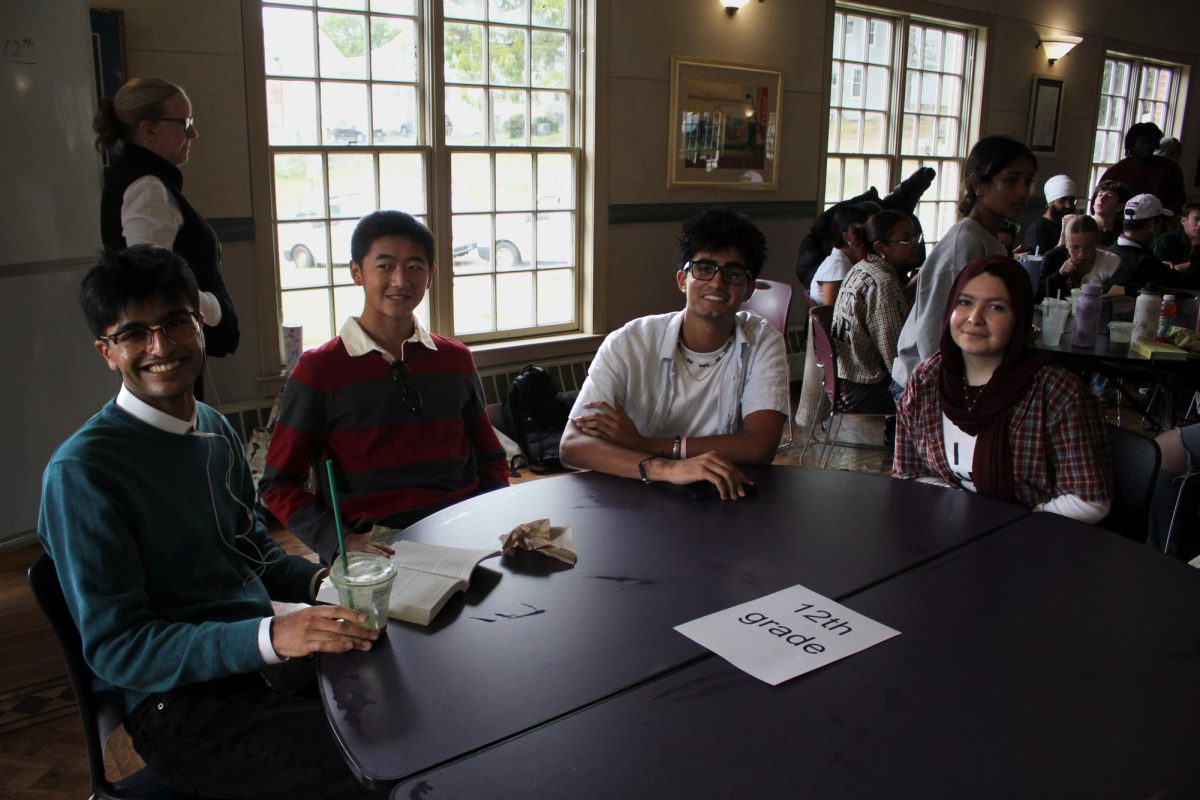

In November, MFS’s Model United Nations club and class traveled to New Brunswick, New Jersey for four days to participate in the Rutgers University Model United Nations Conference. Being the program’s first overnight conference in several years, it was clear that our class’s palpable anticipation veiled a much deeper sense of intrigue, and perhaps anxiety, into not just the proceedings of a full-scale Model UN Conference but the seemingly alien reality of an overnight academic experience.

To say the experience was “difficult” or “rigorous” would be an understatement, yet even after the awards were given and the 1000-plus attendees were sent home, I am confident that there isn’t a single serious attendee who would say the conference was not exhilarating to the fullest capacity. Beyond this, I am doubly confident that there was not a single attendee who didn’t feel that this trip gave them an avenue to improve some skill or push some self-imposed boundary – I know I certainly did.

I’d wager that it’s not uncommon for the standard course of schoolwork to become somewhat banal for students. Assignments blend together as the workload piles, and students are left with no recourse for a shift to a sort of “academic autopilot”; pushing into the second semester and holding out against monotony with the promise of rest, summer, winter break, or just the weekend on the horizon.

It is no surprise then, that when faced with the prospect of a multi-day off-campus excursion, the spirit driving our preparation for the conference was reminiscent of a vigor I personally haven’t felt since my last overnight trip, a one-night stay in D.C. for the 7th Grade Quest Program. Returning to the idea of truly taking learning off-campus for a meaningful amount of time after three years and a pandemic served as a powerful reminder to both my peers and myself. The true advantage of the dynamic, multifaceted education offered by an institution such as Moorestown Friends School isn’t confined to our instructional experiences within the bounds of a classroom, but is rather taken full advantage of when students are given the opportunity to carry the knowledge they have acquired in class and apply it critically to real-world environments.

Yet, even to take this sentiment beyond the mode of direct application involved in testing one’s Model UN skills, which could arguably be viewed as just a more grandiose model of the standard measure of academic acuity, I’m of the belief that there is perhaps infinitely more value posed by situations in which, rather than transposing in-class knowledge onto an off-campus experience, the trip becomes the classroom.

On December 8th, my Spanish class went on a daylong trip to Taller Puertorriqueno, a Puerto Rican cultural museum in North Kensington, Philadelphia. While the main focus of the trip was on the impact that diversity (particularly as a result of immigration) has on a community’s cultural expression, (particularly as can be examined within art) the educational value of the experience in and of itself transcended the information given to us by our tour guide.

For many of my peers, I am confident that our 30-or-so minute mural walk through what we came to learn was called “El Barrio” by its denizens was the first time they’d ever had any meaningfully close experience with urban poverty. Yet, for millions of Americans and many members of our school community, an environment similar to North Kensington is a basic tenet of reality. Yet simultaneously, in being exposed not just to the surface level perspective offered by simply walking through an area such as Kensington, rather having a trip exist in the context of a larger educational experience surrounding the vibrant cultures that persist even within adverse conditions. This grants outsiders deeper insight into the “full-picture” needed to set aside a view of “North Kensington” and gives us the perception needed to understand El Barrio’s culture as the product of myriad factors, not just crime or poverty.

Beyond this, it is an inarguable point that, however informative a lesson is about systemic injustice, a statistical view of the correlation between poverty and crime, or an art history presentation on Puerto Rican culture may be, any of this information is effectively meaningless (certainly less poignant) if it cannot be connected to its impact on actual human experience. If nothing else, this is the true value vested exclusively within off-campus learning experiences.

Whether it be for the purpose of competition like our Model UN program’s trip to RUMUN, the direct augment of our educational pursuits in trips like WordsWorth’s day-long journalism conference at the University of Columbia, or the eye-opening potential for learning when allowing students to inform their learning through experiences such as a first-hand view of how “North Kensington” becomes “El Barrio,” it is clear that off-campus trips have returned in full force as a core tenet of the educational experience in MFS’s post-covid curricula. Regardless of where these journeys may take us, it is clear that, rather than investing more in on-campus experiences, it will be doubly beneficial to focus instead on continuing to globalize our Upper School academic experience through off-campus experiences, not just for their undeniable ability to bolster student morale, but for their imperative role in developing a collective understanding of what our learning means in a post-covid, ever-changing world.