There is a shadow looming over MFS, ominous and inescapable. It starts small, as most great evils do: in the classroom, on the bulletin boards, and in the back of students’ throats, where certain words that long to be spoken die before they ever come out. But this shadow expands, growing with each person it affects, with each voice it silences, until it stretches from the Meeting House to Hartman Hall and swallows us all alive. I am speaking, of course, about the notorious “MFS Bubble.” Head of School Larry Van Meter so eloquently referred to it during his opening remarks to the Upper School on September 9th as a sort of protective sphere, insulating the student body from the harshness of the outside world. And while I would agree with Mr. Van Meter that the so-called MFS Bubble does act as a buffer of sorts, its effect stretches far beyond that of a mere cushion, into territory that is both far more dangerous and much harder to get rid of.

On Wednesday, October 7th, during announcements after Meeting For Worship, Mr. Brunswick cautioned students against putting up messages of their own on club bulletin boards. He pointed out that club members work hard to put those boards together, and cautioned further that posting such a message anonymously is inappropriate. From blank looks spread across the Meeting House floor, I gathered a general sense of confusion among the Upper School body. A sizable portion of the student body has probably barely ever noticed the club bulletin boards, and would certainly not waste their time putting something up.

But I can put the matter to rest myself. Mr. Brunswick was reacting to a message that had been taped to the Gender Equality Forum’s bulletin board by an anonymous student. I, Alex Horn, am that anonymous student. This I freely admit.

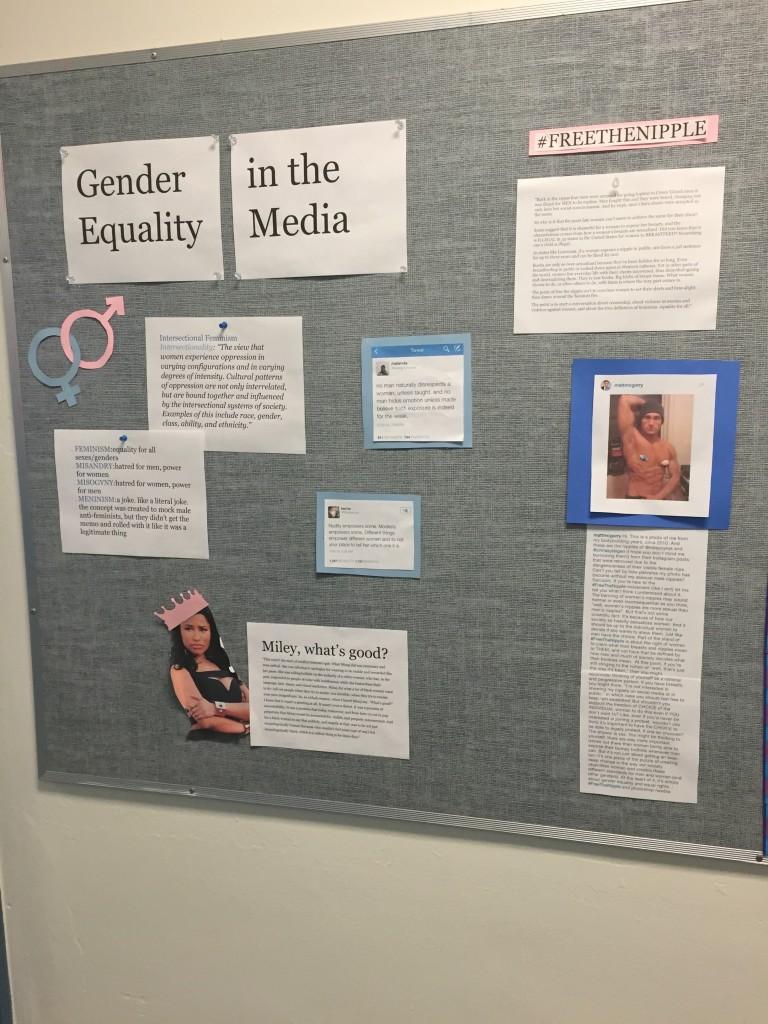

Ultimately, the specifics of why I disagreed with the board’s particular message are irrelevant in light of the broader issue of freedom of expression. However, for the purposes of clarity and context, I will give a brief summary. The board in question, which displayed an amalgam of various quotes supposedly aimed at gender equality, criticized the concept of meninism, a new strain of men’s rights activism that has been divisive within the social justice community, particularly online. I have no particular affiliation with or affection towards meninism, but I was annoyed to see such a complex, arguable issue treated as a simple issue of right vs. wrong, smart vs. dumb, righteous vs. sexist. I was also bemused to see the board’s authors justify their automatic dismissal of meninism by the fact that its name originated as a joke. Consider this: the name “Quakerism,” the core philosophy of MFS, was originally coined to mock the Religious Society of Friends. So I put up a competing sign next to the original, designed to point out both the intellectual dishonesty and the irony I perceived in its composition.

When I read the original bulletin board, I agreed with many of the ideas it presented, in particular the point about the double standard between accepted modes of male and female public bodily exposure. And while I did find some of the points on the board offensive, that alone would not have prompted me to respond—being offended is a healthy, natural, altogether common thing, unavoidable and rightfully so. No, what truly bothered me was not so much the message itself as the tacit implication, intentional or not, that the message had to be accepted as gospel. When I first saw a bulletin board focusing on gender equality, I expected its message to be inclusive of all ideas, denouncing sexism while at the same time allowing for differences of opinion on exactly how that ideal should be practically put in place. I was rudely surprised. Some, although notably not all, of the language on the board was divisive and opinionated, overly political and completely subjective. While I quite support the right of the board’s authors to express their opinions, I was disturbed that the board was posted so blatantly in the middle of a central hallway. It was as if the school administration was saying, “This and only this viewpoint is acceptable.” Much like similarly vague, oft-misused terms like “democracy,” “freedom,” and “class participation,” gender equality (and by extension the related concept of feminism) is an amorphous idea: it means different things to different people.

I contemplated signing my name but decided against it, hoping that leaving the addendum anonymous would make any ensuing discussion more about the issue at hand and less about me. In this I was disappointed: my added poster lasted just a few days before being removed, and while Mr. Brunswick’s warning discussed the practical aspect of releasing such a message, it did not address the actual point I was trying to make. Perhaps I was naive to assume that an anonymous, unbidden message posted on a wall would spark any real discussion. So now I lend my name to my words.

The MFS Bubble is more than the simple cushion it seems to be. At its best it is an anesthetic that numbs us to hard truths; at its worst, a pillow that smothers us before we can speak. MFS is, on the whole, an extremely liberal, extremely feminist, and extremely leftist place. I say that not as if it is a problem that needs to be fixed—those ideas are not at all inherently wrong, and the students and faculty who hold them have every right to do so. The issue comes when the school administration acts as if the opinion of the majority should be the mandate of the entirety. Institutions of learning should be places of exploration, not dogma. No ideology should be held as sacred by school policy, regardless of how many students or teachers hold it as such. I admit without shame that I am sometimes afraid to engage in discussions about sensitive issues, out of fear of being branded a racist or sexist or homophobe, mostly on the basis of my race or gender or sexuality. In the real world, in this country, the open marketplace of ideas allows all ideas to be heard on an equal playing field, regardless of their actual value or legitimacy or political correctness. But at MFS, any idea that could conceivably be considered offensive to anyone is held down in restraint, artificially constricted, which ironically is offensive itself. The opinions prescribed by the school administration, by clubs and teachers and committees, are not the absolute moral truth, and they should not be presented as such. This kind of rigid single-doctrine sectionalism ill-prepares MFS graduates for a life among truly diverse individuals. I believe that I speak for a great number of students on this point, perhaps more than will openly admit it, but here I speak only for myself: The MFS Bubble is holding us down, and it needs to be popped.